Years ago, I remarked that the worsening air quality in Bangkok and its surrounding areas during certain times of the year was partly influenced, to varying extents, by haze pollution resulting from commodity-driven deforestation activities in Cambodia.

After my comment was published in the media, a government agency conducted a modeling study to assert that haze pollution from Cambodia could not possibly reach Bangkok.

However, empirical evidence has since shown that haze pollution knows no borders.

In this Editor’s Note, I examine Thai PM’s recent statement to the media, where she emphasized that PM 2.5 is an international issue requiring regional cooperation. This note questions whether the current measures—such as deploying military personnel and equipment to combat forest fires—are adequate to address the transboundary haze crisis affecting the upper ASEAN region, particularly the air pollution originating from Cambodia.

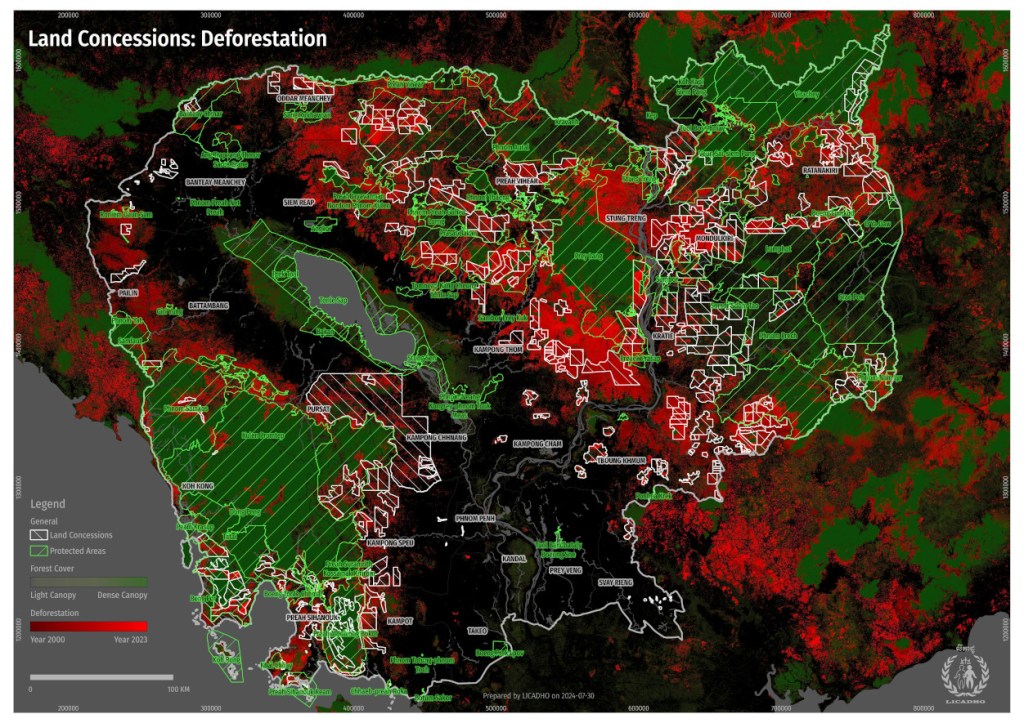

As of the latest data collected up to September 2024, the Cambodian government has granted Economic Land Concessions (ELCs) to domestic and international private investors, covering a total of 330 plots of land. These concessions span 2,247,361 hectares (14,046,006.25 rai), accounting for approximately 12% of Cambodia’s total land area—larger than the entire province of Chiang Mai of Thailand. In addition to Cambodian investors, concession holders also include investors from China, Vietnam, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, and South Korea, with varying levels of involvement.

Around half of the concession areas are used for rubber plantations, with the remainder allocated for sugarcane, pulpwood, cassava, and oil palm cultivation. These concessions have caused significant social conflicts. In May 2012, the Prime Minister ordered a suspension of new Economic Land Concessions (ELCs) and a review of existing ones. However, land disputes remain unresolved, and the government has yet to fully disclose details on the distribution or exact locations of the 2.1 million hectares under current concessions.

According to Global Forest Watch, Cambodia has one of the highest rates of deforestation in the world. Across the country, dense forest landscapes — including those in protected areas — have been cleared for rubber plantations and large-scale logging industries.

Between 2001 and 2014, Cambodia’s annual forest loss rate grew by 14.4%, totaling 1.44 million hectares (14,400 square kilometers).

Research by the GLAD lab at the University of Maryland highlights global rubber price fluctuations and the expansion of land concessions as major drivers of deforestation. Forest loss in concession areas is 29-105% higher than in non-concession areas.

From January to March, the dry season in the upper ASEAN region fuels widespread fires, with Cambodia being a key hotspot. Satellite data links these fires to forest cover loss, which worsens as fire activity increases annually.

Transboundary Haze Pollution Law for the Upper ASEAN Region?

Can Singapore’s 2014 Transboundary Haze Pollution Act (THPA) be applied to address the haze crisis in the upper ASEAN region?

The first answer lies in the political leadership of upper ASEAN countries and their willingness to challenge the region’s strict adherence to the principle of non-interference in member states’ internal affairs—a major obstacle to cooperation, management, and resolution of regional issues.

Singapore’s Parliament has set an example by prioritizing the health of its citizens. The THPA serves as a legal mechanism that breaks through ASEAN’s non-interference tradition.

Importantly, the THPA targets companies, not countries, by holding them accountable for transboundary pollution. For instance, in 2015, Singapore’s National Environment Agency (NEA) issued legal notices to six Indonesian companies suspected of causing forest fires on their lands, leading to haze pollution in Singapore. These actions demonstrate the THPA’s direct application in holding businesses responsible for transboundary environmental harm.

Applying such a model in the upper ASEAN region would require strong political will to adapt similar frameworks and enforce accountability for transboundary haze pollution.

Is the Thai government and parliament ready to take the lead on this issue? Are Thai businesses investing in neighboring countries prepared to raise the standards of their business models?

Another key solution lies in the readiness to implement traceability systems to deter companies or entities, both within and outside host countries, from engaging in activities that cause transboundary haze pollution affecting the public.

In Singapore’s case, the National Environment Agency (NEA) and the courts have the authority to request concession-related information from companies, including spatial data identifying those involved in oil palm and fast-growing tree plantations for pulp and paper along the supply chain. This system operates independently of Indonesian agencies. It also includes provisions for imprisonment and/or fines for polluting companies, their affiliates, and/or suppliers responsible for environmental harm.

For Thailand to lead, it would require adopting similar robust legal mechanisms and corporate accountability measures to combat transboundary air pollution effectively.

In the upper ASEAN region, as far as we know, there is only a database for Economic Land Concessions (ELCs) in Cambodia. This allows us to identify domestic and foreign private companies granted land concessions for large-scale agricultural investments.

In Thailand, major private businesses are attempting to establish traceability systems for their supply chains. However, significant gaps remain, particularly regarding supply chains linked to areas in Shan State (Myanmar) and Laos.

The path toward addressing the haze crisis in the upper ASEAN region, based on the #RightToClean air, is still a long way off. However, we must start taking action today to create meaningful change for the future.