Interviewed by Chonlatorn Wongrussamee

2 PM in the park. Late February. Unseasonal rain drizzles under a gray, heavy sky—the kind of weather that lingers, neither here nor there. It’s in this setting that we sit down with Tara Buakamsri, Director of Greenpeace Thailand, as he prepares to step away from the organization he helped build from the ground up.

Look a little closer, and the backdrop becomes even more surreal, just beyond us, the headquarters of a major fossil fuel corporation and the Ministry of Industry stand in quiet defiance—symbols of everything Greenpeace has spent decades challenging. And yet, perhaps the most surreal thing of all is the thought of Greenpeace Thailand without Tara Buakamsri.

But what’s even more surreal is the multiplicity of identities and ways of thinking that have shaped Tara’s 25-year journey. One might call it the “many cards of a director”—some suited for accomplishing missions, others for fostering warmth and unity, some for fighting battles, and some for standing strong again when inner crises arise.

This conversation invites us to explore the many facets of his identity.

A Rebel

“When we established the Greenpeace Southeast Asia office in Thailand in 1999–2000, the country had just moved past the semi-democracy era, the Black May uprising, and the Tom Yum Kung financial crisis. The media still had freedom of expression, the economy was somewhat stable, and there was an influx of foreign investment, which brought with it environmental problems. That’s why Thailand became the Head Quarter for Greenpeace Southeast Asia.”

How did you localize Greenpeace, an international organization, to fit with Thai society at that time

“Greenpeace was often seen as a network of troublemakers—people who opposed whaling, for example. I believed that Greenpeace’s work in Thai society needed to consider the social and cultural context. If we simply held protest signs, climbed buildings, or disrupted activities, people would wonder, ‘Why are they doing this? It’s inappropriate. It’s not the right time.’ But when we arrived, I just went ahead and did it.”

What was the first environmental issue you took a stand against?

“At the time, the environmental impacts of foreign investment shifting into Thailand had become increasingly apparent. Industrial pollution in Map Ta Phut, Rayong, was becoming a major issue. The first two waste-to-energy power plants were built in Phuket and Koh Samui.

We also witnessed the chemical barrels containing Agent Orange being discovered—left behind by the U.S. military during the Vietnam War—buried beneath Bo Fai Airport in Hua Hin, Prachuap Khiri Khan. At that time, I campaigned against this issue alongside community networks and Penchom Saetang, who is now the director of the Ecological Alert and Recovery–Thailand (EARTH) Foundation.”

Tara once wrote about Agent Orange in a tone that felt almost like poetry :

“…Some say that Agent Orange from the Vietnam War is the most shameful legacy of dioxin in history.

The blood and mother’s milk of southern Vietnam still carry its poison,

and the suffering of disease still haunts American soldiers who fought in the war—

the very soldiers who sprayed nearly 50 million liters of herbicidal toxins, drenching forests, biological resources, and farmlands,

where earth and heaven once met.

Beneath the soil of Bo Fai,

in what they call a “secure landfill?”

we have buried contaminated earth along with moral courage,

along with social and environmental justice,

along with whatever hope we had in those with technical and political power to decide.

They have made us proud to be part of the crimes of the Vietnam War…”

“I was a toxic campaigner. At the time, the government claimed that waste-to-energy power plants were the solution to the overflowing waste problem. But we argued that, in reality, they were ‘cancer factories.’ These plants released various toxic heavy metals—both directly from the waste and from the ash produced by incineration. Among them was dioxin, a known carcinogen.”

Tara’s first major adversary as a campaigner was hence dioxin—a chemical that had caused Vietnamese mothers to give birth to deformed babies with neurological and organ abnormalities. Many mothers also suffered miscarriages. Tara had once described its devastating effects in writing: “The blood and mother’s milk of southern Vietnam still carry its poison.

And, of course, if waste-to-energy power plants were built in Thailand, Thai mothers’ blood and milk would be contaminated with dioxin too. That was something Tara simply could not accept.

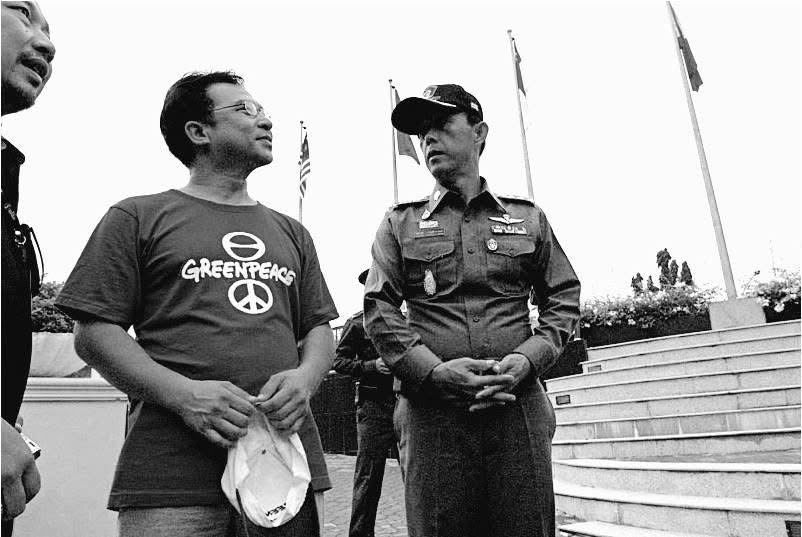

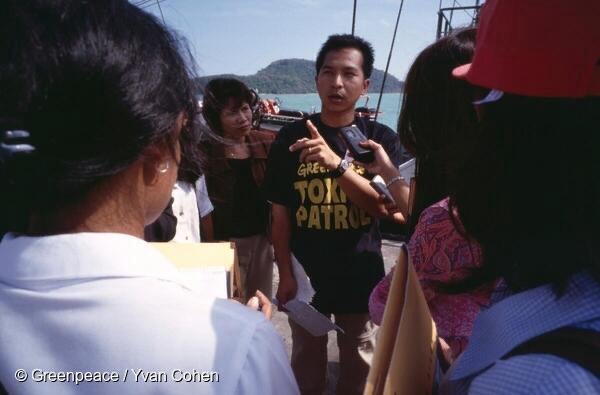

“Our operation at the time involved bringing the Rainbow Warrior to dock in Phuket and Koh Samui, part of Toxics Free Asia Tour. We invited people to visit the ship and learn about the impacts of waste-to-energy power plants. We also staged a protest by placing banners at the landfill site where incineration ash was being dumped in Phuket.”

After conducting scientific studies with a laboratory team from the University of Exeter in the UK, we took the incineration ash from Phuket and Koh Samui and returned it to the front of the Japanese Embassy. This was because Japan’s Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) had funded these waste incineration technologies. We even hung a large banner on the JBIC building near the Ratchaprasong intersection.

As a result, JBIC withdrew its loan for building the waste incineration plant in On Nut and instead provided funds to Bangkok for Zero Waste initiatives—turning waste into zero. As for the Japanese Embassy, we wanted to send a strong message to the Japanese government as a whole: they should stop exporting dirty technologies, electronic waste, and plastic waste to Southeast Asia.”

This was one of Tara’s first acts of defiance under the Greenpeace banner—and, of course, many more would follow.

An Adorable One

Tara’s nickname is “Look Nam” (which means “larva” or “water baby” in Thai). He explained how he got the name: “My father gave me this name. He called me Look Nam, which is a term older people use. But later, I thought, if I get older and people still call me Look Nam, it might not sound very suitable. So, I decided to let people just call me ‘Nam’ instead.” (laughs)

Both his name and his personality seem to match, as Tara once shared : “I was a very shy kid—lacking confidence, unaware of things, not good at speaking, always a step behind everyone else. If I were a student, I’d be the one sitting at the back of the classroom. But I relied on perseverance—falling and getting back up, losing and fighting again. What they call GRIT (Growth, Resilience, Integrity, Tenacity). And that’s what made me who I am today.”

Can you describe what it was like working at Greenpeace in the early days, when many people still called you ‘Look Nam’?

“Back then, our team consisted of just three people. One was handling the paperwork to officially register Greenpeace as a nonprofit foundation, and another—an Indonesian colleague—was coordinating with other offices. Because our team was so small, we had to rely on volunteers. We slowly started inviting friends to join the work. Our volunteers came from both Thailand and various other countries. We began with simple advocacy campaigns, focusing on pollution issues.”

Tara’s idea of giving volunteers “simple” tasks in the early days meant holding protest signs. But over time, it evolved into training for Non-Violent Direct Action (NVDA)—preparing volunteers to become full-fledged Greenpeace activists.

These actions included mobilizing activists from Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Europe to climb construction cranes at the BLCP coal power plant in Map Ta Phut, where they hung banners reading “Stop Coal.” The Rainbow Warrior was also used to block coal shipments imported from Indonesia and Australia.

Activists even set up camps on high-voltage transmission towers that were not yet connected to the grid, using the action to highlight the climate crisis caused by dirty coal—sending a message all the way to international climate negotiations on the other side of the world.

We asked him to share more about these “simple” tasks.

“Our operation was to climb up to the chimney of the BLCP coal power plant, but we didn’t succeed because the plant’s security was alerted and blocked us beforehand. The BLCP coal power plant in Rayong is located in the reclaimed land area of Map Ta Phut. Originally, it was a joint venture between China Light and Power (CLP)—a major energy company in Hong Kong—and Thailand’s Banpu. It was a private power plant included in the country’s Power Development Plan (PDP) and was financed by the Asian Development Bank (ADB), as well as export credit agencies from various European countries.”

“BLCP is a large Independent Power Producer (IPP) included in the national energy plan (PDP). Once its Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) was approved, the project moved forward rapidly with little opposition, as it was located within an industrial estate. This was different from the Ban Krut and Bo Nok coal power plant projects, which were near local communities. In those cases, villagers put up a strong fight and ultimately succeeded in stopping the projects—but at a great cost. The struggle led to the loss of Charoen Wat-aksorn’s life and the imprisonment of Jintana Kaewkhao. Another coal power plant in Map Ta Phut is Gheco-One, which is linked to Banpu and coal mines in Indonesia and Australia.”

Tara’s eyes sparkle with the joy of life, and he always carries a smile. Most people find him warm and easy to talk to—even coal power plant staff. “We carried out operations at coal power plants in the Map Ta Phut industrial estate many times—so often that people started recognizing my face. One time, a plant staff member greeted me and said, ‘Oh, you’re back again? Have you gained weight?’” (laughs)

“We used the issues of coal power plants and industrial development in Map Ta Phut (Rayong), Mae Moh (Lampang), and the southern region as the center of debates on energy direction, greenhouse gas emissions, and the climate crisis. We highlighted the urgent need for a transition to a sustainable and just renewable energy system.

We pressured the Asian Development Bank (ADB) to stop financing coal projects, sent representatives from Map Ta Phut communities to attend China Light and Power (CLP) shareholder meetings in Hong Kong, and testified before the Belgian Parliament about the role of Export Credit Agencies (ECAs) in funding dirty energy. We also conducted field research with communities affected by coal mining in Kalimantan, Indonesia, to expose the human suffering embedded in the global coal supply chain. And, in a symbolic act, we returned coal to Banpu’s headquarters on Phetchaburi Road.”

“It was an era when coal was booming, making it extremely difficult to halt large-scale projects that were already under construction. (The only exception was the Khlong Dan wastewater treatment project in Samut Prakan, which was shut down due to undeniable corruption scandals.) Despite our full-scale opposition to both coal power plants, we couldn’t stop them. The best we managed was pushing China Light and Power (CLP) in Hong Kong to sell its stake in the BLCP coal plant and reinvest in renewable energy in Australia.

Meanwhile, Banpu, one of Asia’s biggest coal giants, eventually expanded into renewables, though it continued to maintain its coal operations. Trying to stop major projects in Map Ta Phut felt like turning the tide. The real turning point for the coal era in Thailand came when we successfully stopped the Krabi coal power plant project. After that, the anti-coal movement gained momentum. Any new coal project now had to secure a social license, and the shift toward renewable energy truly began to take hold.”

On the Wild Side

Many people see Tara as a warm and friendly person—until he does something that leaves everyone speechless. Among the many unforgettable moments in his activism, one stands out: the time he snatched the microphone from a nuclear energy expert. This isn’t a story Tara is eager to share publicly. But we asked him to talk about what inspired him to take such bold action.

“It was sometime after 2009, when the Administrative Court ordered the government to temporarily suspend 76 projects in the Map Ta Phut industrial estate and surrounding areas for failing to fully comply with Article 67 of the 2007 Constitution. A major public forum was held in Bangkok, and at one point, there was a discussion about nuclear power plants in the national energy plan.

A nuclear expert stood up and said that nuclear radiation isn’t dangerous at all—that people living near nuclear power plants receive less radiation per year than a CT scan. He went on to say that he had worked in the nuclear industry for 20–30 years and still had children. But the moment that really set me off was when he said something along the lines of: ‘Any woman in this room who wants to know if that’s true can sleep with me.’ I was furious. I stood up, walked over, grabbed the microphone, and told him to take back his statement, which was a blatant display of toxic masculinity. Later, he sent a letter to the forum organizers, complaining about my so-called inappropriate behavior.”

“Anyone who has followed Tara’s work closely knows that, while he often presents his principles with a soft-spoken approach, he also has a sharp tongue when needed. When we asked him where he gets his boldness, he said it had built up over the years and was something he learned from people in resource-rich communities—especially the villagers of Bo Nok and Ban Krut, whose fiery rhetoric had once left him speechless. Without realizing it, he had absorbed their way of speaking.

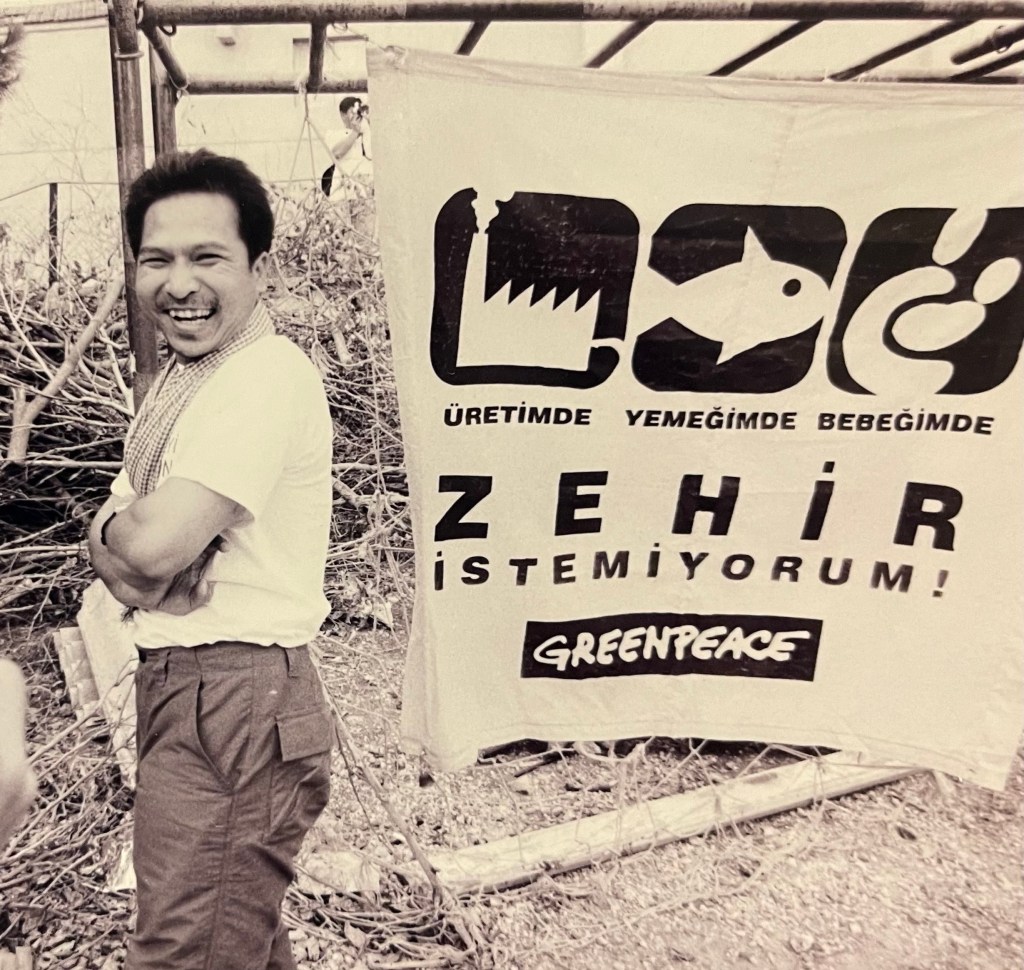

Another environmental battle that wasn’t exactly ‘polite’ was the fight against genetically modified (GMO) papaya. Cornell University had used Thailand as a testing ground for Monsanto, the company that held the patent. Greenpeace carried out investigative research and direct actions multiple times to grab public attention, synthesized scientific data rigorously, and ultimately took the fight to the courts.”

“The issue began when the Department of Agriculture conducted research to develop genetically modified (GMO) papaya resistant to the ring spot virus. The trials were conducted in an open-field setting at the Tha Phra Horticultural Research Station in Khon Kaen, which posed a risk of genetic contamination. Before the GMO papaya case, there had already been an incident involving the contamination of Bt cotton, a GMO crop owned by Monsanto, in 1999. This was exposed by the Biodiversity Sustainable Agriculture Foundation (BioThai), led by Withoon Lianchamroon, along with a network of farmers. In response, the government at the time issued a temporary moratorium on GMO field trials under a Cabinet resolution in 2001. Back then, anti-GMO campaigns were gaining momentum worldwide, from Latin America to India. The development of GMOs was met with numerous questions—about yield, environmental benefits, and strong consumer rejection.”

“Within our campaign team, we agreed that this issue needed to be brought to public attention. At the time, Phattawadee Srisuwan was the lead campaigner. We planned a direct action, sending in a team of highly disciplined and well-trained activists, fully equipped with protective suits and masks, into the horticultural research station in Khon Kaen. They collected the GMO papaya plants—including the stems, leaves, flowers, and roots—and sealed them in airtight containers. On one hand, this Greenpeace action was heavily criticized for being too extreme. I still remember that some NGOs did not support this approach. But for us, even if it meant taking risks and facing consequences, this was a battle where food sovereignty was at stake.”

“That operation intensified the debate on genetically modified organisms (GMOs) in policymaking. In 2004, the National Human Rights Commission issued a statement confirming that GMO papaya had already escaped and spread into the environment, contaminating the Kaek Dam Tha Phra papaya variety. The commission also expressed its support for the government’s decision to prohibit field trials of GMOs, whether in state or private research stations or on farmlands.”

“The Department of Agriculture filed a lawsuit against Dr. Jiragorn Kochaseni, Executive Director of Greenpeace Southeast Asia, and Phattawadee Srisuwan, the campaigner at the time, accusing them of trespassing and damaging property. The case went to the Khon Kaen Criminal Court and later to the Court of Appeal. In 2009, the court dismissed all charges, citing the right to environmental protection under the 1997 Constitution. Tara stated, ”We fully exercised the Constitution to affirm our right to protect the environment.“

“Years after the battle against GMO papaya, many of Tara’s colleagues left Greenpeace, but he remained steadfast—first as Country Representative and later as Country Director. Along the way, he faced numerous decisions: whether to follow the conventional path or to push beyond the comfort zone. One such moment came in 2015, when Greenpeace Thailand’s campaign team conducted an investigative research on human rights violations and illegal fishing in Thailand’s distant-water fishing industry. The findings led to the release of a highly controversial report in 2016.”

“The investigative research took 12 months to complete and detailed cases of Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated (IUU) fishing in Thailand’s distant-water fishing industry. The report exposed the trafficking and forced labor of crew members who were subjected to inhumane working conditions—so severe that diseases long thought to have disappeared in the 19th century re-emerged. It documented fatalities at sea due to negligence on Thai fishing vessels operating in the Indian Ocean, as well as destructive fishing practices that harmed fragile seagrass ecosystems. The investigation also uncovered illegal at-sea transshipments, where seafood was transferred between vessels without authorization. This report forced Tara to make a major leadership decision as the head of the organization.”

“There was a social media backlash, accusing us of being ‘traitors to the nation.’ But the real issue that escalated into a SLAPP lawsuit was the pressure to remove certain content from our report—content that was factually accurate and properly sourced but considered too sensitive. Before publishing the report, our legal team had scrutinized every single line, from the first page to the last. They told us outright, ‘We’re definitely going to get sued.’ (laughs) When we received the lawsuit, the pressure was intense. But our legal team stood firmly with us. In the end, the prosecutors decided not to take the case to court. This investigative report gave us the courage to speak truth to power—so much so that major players in the fishing industry had to publicly distance themselves from illegal practices and commit to making the industry more responsible.”

A Campaigner

If you’ve followed Tara’s journey this far, you’ll see that Non-Violent Direct Action (NVDA) is just one aspect of his work as a campaigner. His approach combines strategic activism with scientific analysis and synthesis, public communication, and resilience under pressure—and that’s only part of the story

“The role of a campaigner is often misunderstood. There’s a story about an environmental engineer who applied to be a campaigner for Greenpeace UK. When he told his colleagues in the engineering field, they were shocked and thought he was crazy—saying that his career would be ruined.”

So, what does a campaigner actually do?

“It’s an incredibly challenging profession. Everyone at Greenpeace undergoes rigorous training. Campaigning is primarily about communicating and engaging with society—persuading large numbers of people to take urgent action. It is a form of participatory democracy, meant to serve the public interest. Most importantly, campaigning creates space for change—giving the public a role in shaping society. Campaigning blends multiple disciplines—law, science, literature, sociology, and politics.’

But effective campaigning follows key principles : Show, don’t tell—it’s about demonstrating impact rather than simply stating facts. Motivation rather than education—inspiring action rather than just sharing knowledge. Mobilization rather than accumulation of knowledge—activating public energy and opinion rather than just collecting information. This work opens your eyes. Campaigning gurus have always told me that effective campaigns must be systematic and that communication planning is just as meticulous as writing a song or directing a film.”

“One of the mantras I use in campaigning is that we must foster participation and agency—empowering people to take control of their own lives and make decisions. To achieve this, we need to present credible, feasible, and compelling alternatives that drive fresh and meaningful change.” When it comes to campaigning, Tara’s special focus is on corporate campaigning—an area of activism that directly engages with power dynamics and corporate accountability.

“Beyond understanding communication and motivation, a campaigner must grasp the dynamics of power. They need to identify who controls what and who benefits from the status quo. They must ask: Why hasn’t the change we seek happened yet? When existing power structures and vested interests are challenged, people start paying attention. For a campaign to reshape politics and power structures, it must be built on a well-planned strategy that understands the interests behind power.”

One corporate campaign that exemplifies strategic power analysis, as Tara describes, is the push to strengthen human rights protections in Thai Union’s seafood supply chain. We asked Tara to share more about this campaign.

“At the time, the big question was: If we wanted to make the seafood supply chain free from human rights violations—from fishing vessels to dinner tables—where should we start? The system was massive and highly complex. Then, I came across a study titled Transnational Corporations as ‘Keystone Actors’ in Marine Ecosystems, which provided a clear strategic direction. The study used a simple analogy: A keystone is like the central stone in an arch—strong and seemingly unmovable, but if you remove it, the entire structure collapses.

Another study pointed out that Thai Union was the largest canned tuna company in the world. On supermarket shelves, particularly in Europe and North America, one in every five cans of tuna was produced by Thai Union. At the same time, Thai Union had just begun implementing sustainability policies in the fishing industry and conducting human rights due diligence. This made them both a symbol of Thailand’s global role in the seafood industry and a keystone actor—one of the crucial stones in the arch.”

“Beyond investigative research into the seafood supply chain, this was also a global campaign coordinated between Greenpeace Thailand, the U.S., Canada, Europe, New Zealand, and East Asia from 2015 to 2017. We deployed every strategy available: ranking seafood sustainability, mobilizing consumers, working with maritime labor unions, protesting at seafood industry conferences, documenting testimonies from migrant workers on distant-water fishing vessels, using technology to track deep-sea fishing fleets, and witnessing firsthand the hundreds of thousands of pieces of destructive fishing gear scattered across the Indian Ocean. Most importantly, negotiation played a crucial role. I was part of the negotiation team, and we went through multiple rounds of talks in Bangkok, London, Brussels, and San Francisco. After reaching an agreement, independent auditors were brought in to assess progress, and we published a final report in 2020.” **

“The negotiations resulted in an agreement that led to positive changes in the fishing industry across four key areas: 1. Destructive fishing gear (such as purse seines using fish aggregating devices – FADs) 2. Longline fishing 3. Transshipment at sea 4. Labor rights. Meanwhile, Greenpeace’s human rights and illegal fishing report—which we refused to redact—became a powerful bargaining tool in negotiations with the world’s biggest tuna corporations. At times, stepping back was necessary, but in other moments, standing firm was critical. For Tara, this was always about turning the tide—navigating the waves carefully, knowing when to push forward and when to hold the line.”

“What I’ve learned from negotiations is that aligning interests doesn’t mean compromising. Greenpeace has a clear stance, but even conflicting positions often share some public interest—and it’s our job to find that common ground. As for whether our agreement with Thai Union will create ripple effects across the fishing industry, only time will tell. It’s similar to coal—once seen as an essential energy source, but now nobody wants to invest in it because it has become history.

Beyond engaging with corporations, another key role of a campaigner is responding to moments that could become turning points in a campaign.”

”It might not work, but it’s better than being too late.” That’s how Tara describes seizing the moment—a skill that has made the difference in many successful campaigns. “Often, we need to use what I call a Disruptive Moment—our golden opportunity, but a nightmare for the other side (laughs). These moments push our campaigns forward in leaps, rather than in a straight line. Campaign issues don’t move linearly. At some point, people get bored or stop paying attention. There’s a saying that politics is the art of the possible. But—as I see it—campaigning is both a science and an art of making the impossible happen. We have to find a way to keep going.”

Was there a time when you felt you seized a disruptive moment at the right time?

“Yes—the issue of toxic PM2.5 pollution. We had been campaigning against coal for years, and one of the pollutants from coal-fired power plants is PM2.5. But for a long time, no one really paid attention. Then, a debate started in Chiang Mai—why was the U.S. Consulate there measuring and reporting PM2.5 levels, but the rest of the city had no data? In Bangkok, there was one particular day when everyone flooded social media with posts about a thick fog, even though it wasn’t winter. People were struggling to breathe and feeling unwell. That moment—when the public was questioning what was happening—was the perfect disruptive moment. We used that momentum to inspire the public, explaining that it wasn’t just fog—it was toxic PM2.5 pollution. From there, we pushed the Pollution Control Department to update the Air Quality Index to include PM2.5 and to tighten ambient air quality standards”

Which is more effective—running a campaign step by step or seizing a Disruptive Moment?

“From my experience, disruptive moments have a higher chance of success. According to dialectical materialism, change happens when quantity transforms into quality—not in a straight line, but through tipping points and critical mass. When those moments are reached, the old system collapses, making way for a new one. As I mentioned earlier, campaigning relies more on mobilization and public opinion than just accumulating knowledge, to seize a disruptive moment when it suddenly appears, you need intuition—sometimes you have to improvise. But at the same time, you need a diverse set of strategies ready to deploy in almost any situation. And most importantly, you have to be bold enough to take risks at the right time. It might not work, but it’s better than being too late. If we hesitate, a sudden political shift or another crisis could push our issue out of the spotlight, and it may no longer be seen as urgent.”

An Activist

If someone casually drops the word “dialectic” into a conversation, you can make two assumptions: they’re either well-read or they lean left politically. So, we asked Tara about this.

“I was born in Aranyaprathet, on the Thai-Cambodian border, in 1967—the same year ASEAN was founded. When I was 7 or 8 years old, the Khmer Rouge took control of Cambodia, leading to a prolonged civil war and a wave of hundreds of thousands of war refugees along the border. Cambodia didn’t find any real stability until the Hun Sen regime was established—by then, I was already an adult.”’

Growing up in such an extraordinary environment sparked curiosity in Tara and, at the very least, instilled in him a desire to make the world around him a better place. That small thought took root—thanks, in part, to the encouragement of a guidance counselor who saw his potential.

“I became interested in environmental issues during high school at a provincial school in Samut Prakan. There was a guidance counselor who had been an activist during her university years at Silpakorn University. She assigned us to create a zine about the first-ever Earth Summit in 1972, held in Stockholm—officially known as the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment. It was a UN gathering where activists, hippies, business leaders, and government representatives all came together. That summit also marked the first-ever use of the term Biosphere.

“The zine I created told the story of our world, which was beginning to face an ecological crisis. It was part of a guidance counseling activity, where the teacher used it as a tool to help students understand life and society. When I went to university, I naturally gravitated toward the Nature and Environmental Conservation Club. Back then—40 to 50 years ago—student activism wasn’t as diverse as it is today.”

What kind of student were you back then?

“At the time, General Prem Tinsulanonda was Prime Minister, and Thailand was under a semi-democracy. The student environmental movement was still thriving, with its roots tracing back to the Thung Yai Naresuan wildlife hunting scandal, which was closely tied to political changes. I was involved with the Committee for Natural Resource Conservation of 15 Institutions, a student network focused on environmental issues, which operated alongside the Student Federation of Thailand—an organization that focused on political and social activism. During that period, major environmental conflicts were unfolding, such as the Nam Chon Dam project, which was planned inside the Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary, the expansion of fossil fuel extraction in the Gulf of Thailand as part of the Eastern Seaboard Industrial Development Plan.”

“After the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in the former Soviet Union, the world became acutely aware of the threats posed by radioactive contamination. This heightened environmental awareness in Thailand as well, leading to mass protests against the Tantalum smelting plant in Phuket. The situation escalated into a tragedy when the plant was set on fire in June 1986. This was one of the first major instances of public resistance against a state-backed industrial project in Thailand—a costly lesson on industrial pollution for Thai society. It also revealed a stark reality: violent expressions of collective will often emerge before democratic systems fully recognize the people’s right to express that will. Even today, this serves as a reminder that when mechanisms for public participation are excluded from national development, social conflicts remain unresolved.”

At what point in your life did you truly experience the realities of environmental impacts on local communities?

“During my university years. At first, I was involved in nature conservation camps—hiking, birdwatching, and studying forests. But then, I became aware of land grabs and the seizure of community resources in Northeast Thailand for eucalyptus plantations. That shifted our focus to community forest camps instead. At the same time, dam construction projects—like Nam Chon Dam, Chaew Lan Dam, and Kaeng Sua Ten Dam—pushed us, as students, to go into the field and learn directly from communities resisting these projects.

After finishing my undergraduate degree, I entered a period of searching for meaning in life. I lived with local communities in Ban Noen Phayom, Tha Ruea Klaeng (Rayong) and Laem Chabang (Chonburi). These communities were fighting against trawl fishing, mass tourism, industrial expansion, and coastal aquaculture (Blue Revolution). The mangrove forests of Eastern Thailand were disappearing due to intensive shrimp farming, which at the time was an industry as lucrative as the drug trade. Part of my work involved field research, with guidance from Professor Surichai Wun’gaeo, who was a mentor to me. I also had the opportunity to work with Khru Daeng—Tuenjai Deetes, supporting ethnic communities in the mountainous areas of Doi Mae Salong, Chiang Rai. At one point, I worked as an editorial staff member for Moo Baan Newspaper—a small media outlet for community networks. That job took me across villages all over Thailand. Back then, computers weren’t widely available—we used typewriters and wrote our notes by hand.”

Is there any aspect of activism that still influences you today?

“An activist must learn to move beyond their own sense of self. For me, being an activist has shaped how I see Greenpeace in two ways (1) As an organization (2) As part of a broader social movement. The Greenpeace brand is strong, and there are times when people expect us to take on every issue. But as a social movement, once we’ve worked on an issue long enough for it to become a societal norm, a mainstream conversation, or a widely accepted framework, our role shifts. At that point, the issue no longer needs to carry our name—we must use that foundation to push for further change in other areas. We don’t need to be recognized, we don’t need likes or shares all the time. Activism isn’t just about posting online or performing symbolic actions. Activism needs roots. It must be grounded in class struggle, because—as the saying goes: “Ecology without class struggle is gardening.”

Are you on the left? And why do you always sign your emails with In Solidarity?

“Beyond just left or right, environmentalism itself has many shades—deep green, moderate, light green, surface-level green. I believe that categorizing people based purely on political theory doesn’t quite fit in today’s world, which is becoming increasingly chaotic and unpredictable. But what’s certain is that I align with the framework of political ecology—because democracy and environmental issues are fundamentally connected. If we want the environment to be a truly public issue, we must integrate it with public participation and democracy.”

“Many people ask why I connect Greenpeace with politics. Why do I talk about democracy? To me, politics is the stage where public policies are decided—a political opera. Greenpeace is an independent environmental organization, but if we want to change policy, we must understand politics. When a government does not come to power through democratic means, public policies often become corrupt, leading to social and environmental disasters.”

Of all the roles you’ve taken on, which one do you like the most?

“Honestly, I enjoy being an activist the most. Just talking about data or lobbying isn’t as exciting—it doesn’t engage the body and energy in the same way. Being an activist helps me see the world with hope. Sometimes, we feel stressed, sad, or overwhelmed because we’re stuck in problems, constantly searching for solutions. But activism allows me to find joy in the struggle—it brings out the human side of the work. An activist should be as human as possible.”

And what about In Solidarity—why do you always use it to sign off your emails?

”In Solidarity comes from the labor movement in Poland. When I was a student, I engaged with political activists, and I came across this phrase—I really liked it. It helps set the tone that no matter what happens—whether we agree or disagree—we must stand in solidarity if we want to create change. And honestly… it just sounds cool.”

A Human Being

You’ve said that you’ve failed more often than you’ve succeeded. Can you share more about that?

“I believe success is just a construct—something we invent in this world. I’ve encountered a lot of failures. Sometimes, the things I put so much effort into simply don’t work. I’ve often felt, ‘Why did I pour so much energy into this when nothing seems to change?’ Issues that existed 20 or 30 years ago are still happening today. But I’ve never told myself, “That’s it. I’m done.”

So how do you deal with failure?

“The moments when I’ve failed are actually the moments I cherish most in my work. My time at Greenpeace has been full of risks and experiments. But when I’ve fallen, there have always been people who understood and supported me—my family, friends in Greenpeace, fellow activists, and allies in communities. Burnout comes when we give everything we have and push ourselves too hard. But discouragement fades when we have solidarity—no matter what condition we’re in. Whether we’re heartbroken, crying, laughing, or celebrating, there is always a space of support that helps us recover, regain energy, adapt, and stay resilient. That’s what allows me to stand firm, stay strong, and not be shaken by pressure.”

How important is this space of support?

“Oh, without it, I don’t know why I would keep going. I believe that a space that embraces those who are committed but make mistakes is just as important as the actual work of creating social change. This space is bigger than campaign successes—it’s what makes the fight for environmental justice more sustainable and allows for new experiments to happen. Every social movement needs this kind of space because social change is never easy. The path is full of obstacles and thorns.

When we lose our way, we often argue and blame each other—“You got us lost!” (laughs). Some might say, “Forget it, I’m done.” But if we can tell each other, “It’s okay, we’ll find our way back. Maybe there’s a shortcut, maybe there’s an even better path—one with fewer obstacles but still leading to the same goal”—then we free ourselves from fear. We must be bold enough to seek new paths. Getting lost is just a way of exploring new possibilities.”

How would you describe your 25-year journey with Greenpeace Thailand?

“Like a caravan traveling across long distances, facing endless obstacles. There hasn’t been a single day without problems (laughs). But we have to make decisions, stay determined, and push forward—just like a caravan that, when lost, looks up to the sky to find the North Star.

But sometimes, I also compare myself to Charlie Watts : The subtle magnificence of the Rolling Stones’ drummer once said: “5 years of work, and 20+ years of hanging around. So it makes me wonder… how much of my time was actually spent working? And how much was just hanging around? (laughs)”

What do you see for the future of Greenpeace? And where will your North Star take you next? We asked him our final question.

“I consider myself incredibly lucky to have worked with Greenpeace. I’ve been able to use every skill I have—science, research, law, negotiations, communications, and hands-on activism. I’ve lived my life to the fullest, making the most of the time I’ve been given. But now, it’s time to pass Greenpeace Thailand on to a new generation of leaders—passionate, determined, creative, and sharp-minded individuals. We will see a new era of Greenpeace campaigning, one that fits the realities of today, without being bound to the past.”

What’s next for you?

“I plan to write about my experiences in the environmental movement—documenting these past 25-30 years—and offer guidance to those who are determined to create change, wherever it’s needed. No matter where I am, in whatever role, I will still be just one worker ant in the vast movement for social change. I believe many people share the same vision as I do—a vision of a better Thailand, a better world, where people live in a healthy environment, with basic rights, clean water, fresh air, and the freedom to speak their minds.”

As our conversation came to an end, there was one last phrase—one that many who have crossed paths with Tara in the fight for the environment would probably want to say to him…

In Solidarity.