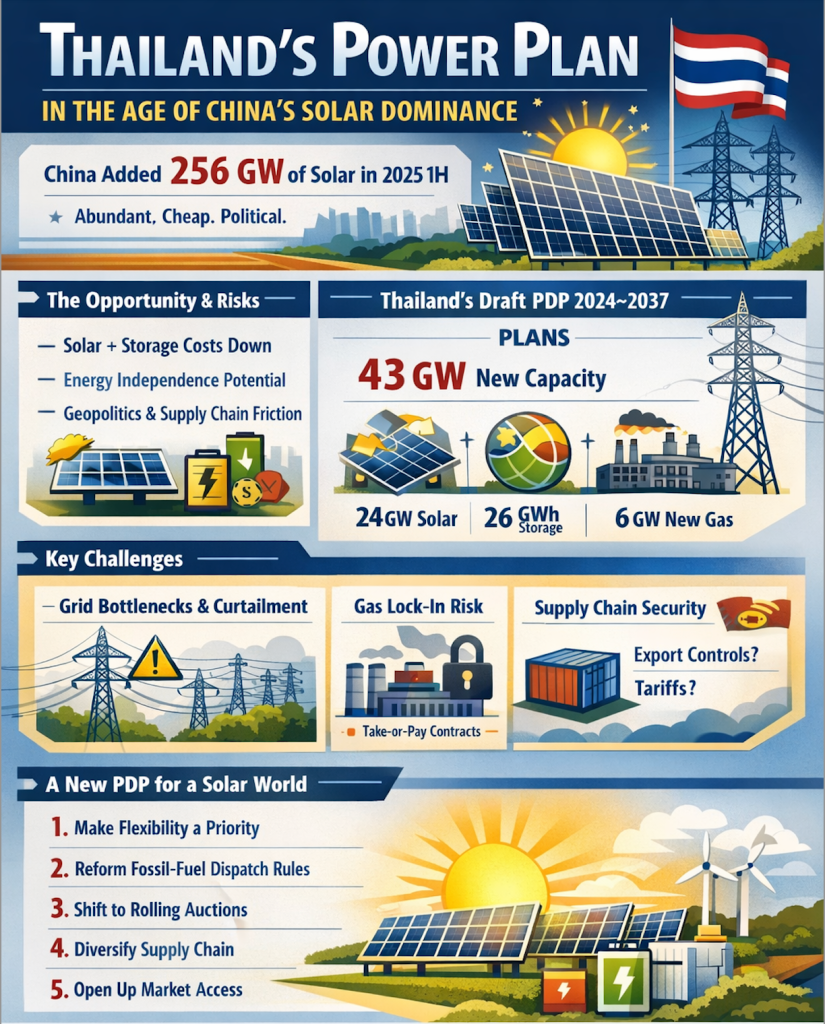

Thailand is drafting a new Power Development Plan (PDP) at the exact moment the global electricity system is being reordered by one fact: China has made solar power not merely cheap, but structurally abundant. In the first half of 2025 alone, China added roughly 256 GW of new solar capacity—an expansion so large it outpaced what most power systems (including China’s own) can comfortably absorb.

For Thai policymakers, this is not an abstract story about distant factories. It is a direct stress test of the assumptions embedded in the PDP now being developed, including PDP2024 (2024–2037), which was presented through the Energy Policy and Planning Office (EPPO) public hearing process in June 2024. (eppo.go.th)

The solar era is no longer defined by scarcity. It is defined by system constraints.

China’s rise is not just scale—it is dominance across the supply chain. The paper The implications of China’s solar dominance notes that China now dominates every major segment, “from polysilicon and wafers to modules and inverters.” That industrial machine can produce far more equipment than the domestic grid can absorb, driving prices and margins to historic lows—and forcing Beijing to confront curtailment, market disorder, and the political backlash of “involution” (destructive overcompetition).

For Thailand, the key implication is counterintuitive: the constraint on solar is increasingly not the panel price—it is the grid, the rules, and the contracts. If Thailand fails to modernize its system architecture, it can end up buying ever-cheaper equipment only to curtail clean power or lock it behind bottlenecks.

Thailand’s draft PDP points in the right direction—then hesitates

On paper, Thailand’s draft PDP2024 contains the outline of a modern plan. BloombergNEF’s assessment of the draft PDP notes a call for 43 GW of additional capacity (2024–2037), with 24 GW of terrestrial solar and significant flexibility resources including 26 GWh of battery storage and 20 GWh of pumped hydro.

But the same draft also includes new gas capacity—6 GW of additional combined-cycle gas turbines (CCGTs)—and does not commit to retiring existing coal. In other words: Thailand is planning for a solar future, but still keeping one foot in the logic of the gas era.

That hesitation is understandable. Gas is often treated as “security.” Yet security today is not only about fuel supply; it is about cost volatility, delivery risk, and the ability to integrate domestic clean power at scale. And here the economics are increasingly unforgiving: BloombergNEF finds that solar paired with battery storage is already cheaper than new coal and gas plants in Thailand, and even suggests solar can undercut the operating cost of existing gas in certain cases.

China’s solar dominance adds a second complication: geopolitics

If low prices were the whole story, Thailand could simply accelerate auctions and build. But the paper makes clear that the global solar market will be shaped “as much by politics as by price.”

Beijing has expanded a “foreign-related legal toolkit,” including sanctions and blocking mechanisms, alongside “a more assertive export-control regime.” As tariffs and localization mandates spread, Chinese firms increasingly treat them as structural incentives to accelerate overseas manufacturing and third-country hubs, including in Southeast Asia.

This matters for Thailand’s PDP in two ways:

- Supply-chain resilience becomes a planning variable. A least-cost model that assumes frictionless imports is no longer realistic.

- Industrial strategy is now implicit in power planning. Thailand will either become a passive price-taker—or define rules to capture value, jobs, standards, and recycling systems as solar floods the region.

The real danger: “solar on paper, curtailment in practice”

China’s own experience is a warning. Even with extraordinary buildout, coal-heavy provinces and incumbents can shape dispatch rules, making the pace of coal decline “a political question as much as a technical one.” Thailand has its own version of that problem: legacy dispatch practices, grid constraints, and contracts that prioritize thermal generation.

For example, BloombergNEF notes that as of 2023, gas plants supplying most generation have been operating under take-or-pay arrangements—contracts that can incentivize running gas even when cleaner power is available. If Thailand expands solar while leaving take-or-pay and dispatch priorities intact, the system will resist the transition from within.

This is why the PDP’s headline numbers are not enough. A solar-heavy plan succeeds only if Thailand rewrites the operating rules of the power system.

What a “China-solar-world” PDP should commit to

Thailand’s new PDP should be explicit about five commitments—because without them, the plan risks becoming a procurement list rather than a transition strategy:

1) Make flexibility a first-order resource, not a supporting actor.

If the PDP targets 24 GW of solar, it must treat storage, demand response, forecasting, and grid expansion as co-equal, enforceable build obligations—consistent with the draft’s storage ambition (26 GWh batteries + 20 GWh pumped hydro).

2) Reform dispatch and contracts to stop “must-run fossil” behavior.

If take-or-pay remains dominant, solar will be curtailed and consumers will pay for both systems. The PDP must put contract reform and system operation rules on the same level as generation targets.

3) Shift procurement from episodic quotas to predictable, rolling auctions.

China’s 2025 surge was triggered by policy and pricing design, including the transition toward market-based pricing replacing feed-in tariffs. Thailand should avoid stop-start procurement that misses price windows and creates boom-bust cycles.

4) Build supply-chain resilience into planning.

As export controls, tariffs, and localization rules spread, Thailand should plan for supplier diversity and critical-component availability (inverters, transformers, storage cells)—because “dependence in a strategically sensitive sector” is now a central global debate.

5) Unlock clean power demand through market access—not monopoly bottlenecks.

The draft PDP’s investment needs are enormous; BloombergNEF argues Thailand will struggle to meet them if market regulations continue to favor incumbent utilities, and it highlights the importance of expanding procurement options such as DPPAs.

The political choice Thailand must make

China’s solar dominance gives Thailand an opening: decarbonize faster, cut exposure to LNG volatility, and strengthen energy affordability. But it also removes excuses. If solar is cheap and plentiful—and the transition still stalls—then the barrier is not technology. It is governance.

Thailand’s PDP should therefore be judged by a simple test: does it change the power system so clean electricity can actually displace fossil generation in real time, at scale, without curtailment and without contract lock-ins?

A PDP written for yesterday’s world will treat solar as an “add-on.” A PDP written for today’s world will treat solar abundance as a structural condition—and redesign the grid, the rules, and the market so Thailand can use it.